New Entrants Case Study: Joint Ventures for Landowner

5 April 2018Case Study: Stephen Withers and Neil Sandilands

Share Farming – A Different Approach for Owner and Operator

Share Farming is not common in Scotland but two farmers explain how it works for them.

Stephen Withers owns a farm near Jedburgh in the Scottish Borders. It is a mixed holding of arable, cattle and sheep. Different labour sources had been used in the past to assist with sheep work but Stephen retained day-to-day responsibility and management control.

It was not a favoured enterprise and he felt jobs were always being tackled reactively, having competing priorities across enterprises. Meanwhile Neil Sandilands had been providing casual labour at busy times, primarily for sheep work, whilst also trying to build-up his own small flock on seasonal grazings.

With no family wanting to take on the farm, there came a point in time when Stephen either needed to employ a full-time shepherd or seriously review the whole business operation.

“There was a temptation to knock the business into neutral and let it coast along” explained Stephen “but I didn’t want to see the farm in decline. I thought that if I had family interested in farming, letting them take responsibility for some of the business would naturally happen, so why not with someone else, provided you are happy to go into partnership with them?”

How does it work?

From the outset, Stephen set up a separate business partnership agreement with Neil to run the sheep enterprise as a joint venture.

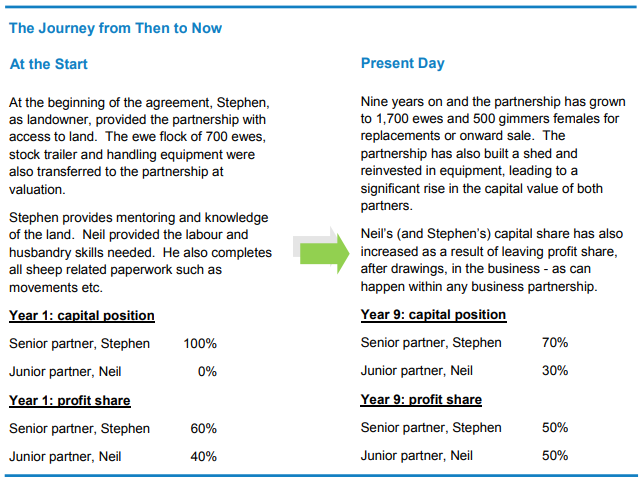

Within this agreement, profit share was initially established at 60:40 but has since increased to 50:50 as both parties took confidence in their relationship and the new business structure and performance. Neil also demonstrated a real willingness to take responsibility and drive the sheep business forward.

A share farming agreement is flexible enough to take various forms. Business performance of any farm enterprise is also dependent on good management, husbandry, market price, the weather and level of private drawings taken. Therefore, the below information only illustrates how it has developed here:

Neil’s capital share has obviously improved as he has driven the sheep business forward but it is important to note that Stephen’s capital share has also increased in real terms (more than doubling) due to expansion, which was unlikely to have been achieved otherwise.

Some would ask ‘why give away capital in your business?’

Both partners can draw a wage from the business while also building capital. Capital growth has allowed the business to grow, further improving profitability for both partners. This required level of motivation may be less likely where using more traditional arrangements such as employed labour or a contract shepherd and would require a higher level of Stephen’s management time, at the expense of other commitments.

It is worth noting that each partner could, in theory, take all of their profit share as private drawings and not reinvest in the business – just like any partner in a business could. However, this would reduce business performance and returns for both partners.

Why Share Farming?

Share farming allows both parties flexibility. From the outset, it allowed both parties to become familiar with the concept of shared responsibility

without Stephen – known as the ‘Share Owner’ – releasing majority control.

It also allows Neil – known as ‘Share Operator’ – to grow organically without the need for a huge amount of accumulated capital. This is more

typical of a genuine new entrant. Since releasing capital was not a factor here, in this case that also meant, Stephen could concentrate on identifying the right candidate and did not need to be restricted to only those with existing finance.

Stephen had available farmland but not the time or desire to work with sheep. This presented an opportunity to make better use of the land and for the right person to drive the enterprise forward.

A contract shepherding arrangement may have worked but the question was whether that would have instilled sufficient motivation to progress the business and it would still have required a considerable level of management.

With Neil having a vested interest in the wellbeing and performance of the flock, the farm is more profitable and has grown significantly.

It is important to appreciate and accept this as a different way of working – it is a partnership.

Stephen, was previously in control of all farming matters. The whole reason for this structure was to delegate responsibility, instill an added level of commitment within someone, and help drive the business forward.

There is a partnership agreement. It outlines expectations, terms and conditions. But not everything can be written down. Trust and compatibility are major factors. Stephen also notes that it is important not to be greedy. The junior partner must make enough and know they are getting a fair return, relative to the lamb trade at the time. Otherwise it can be a disincentive.

The benefits for Stephen (the share owner)

Stephen has found multiple benefits to developing this agreement –

- “The farm [steading and land] is in better heart than it would be without that extra drive and enthusiasm”

- “With the right person it is really satisfying to see a young person making a go of it”

- “It has given me the time to concentrate on other parts of the business. Giving responsibility provides me more control not less, not always feeling as if in crisis mode”

- It works, it is profitable.

- There is no complications with employment law or worries over creating a tenancy.

The benefits for Neil (the share operator)

As it needs to, it also works for Neil –

- “I wouldn’t be in this position without this agreement.”

- “I’ve grown from a small amount of cash but now with capital in the flock giving added incentive to do a good job and keep trying to make it better.”

- “I am essentially my own boss, I have the freedom to build and grow the business, benefiting from scale.”

- “It doesn’t work without trust. The agreement keeps things right, but we already knew each other and that trust is essential e.g. when I am buying a tup or when Stephen is buying the fertiliser – it requires trust in knowing we are both getting the best or right deal.”

FOR MORE DETAILS SEE THE GUIDANCE NOTE: www.fas.scot/new-entrants/guidance-notes/

Share Farming – a summary!

An open and transparent relationship is essential but this must be accompanied by a written document. This also helps define expectations and aspirations from the start.

However, there is no standard share farming agreement. The details depend on the objectives, skills and resources of the parties involved.

Typically the owner provides land (maybe some or all machinery – depending on the starting point of the share farmer) and the share farmer provides

the skill and labour into the enterprise. Partners would then split input costs and sales on a preagreed basis. Resulting profit/loss is similarly split.

Just like in any other farm business, a partners owned capital is not itemised to include specific assets/liabilities. For example, a business partner with a 20% capital share in a share farming agreement, where the only asset is sheep, would own 20% of all sheep and not 20 specific ewes per 100 in the flock.

As best demonstrated through examples from New Zealand, where share farming is more common, it is feasible for a share operator to build sufficient

capital over time to then move and buy into a larger share farming agreement. Alternatively, the progressing share operator may now be better placed to take on a tenancy or contract farming agreement. They may even buy a farm, and likely become share owner, bringing someone else in as share operator.

This then frees the original share owner to change policy or provide an opportunity for a new share operator.

Top tips

- Requires a different mind set – don’t be greedy, everyone has got to live. It is also good if the operator’s share is growing as that benefits the share owner too

- Trust and compatibility – don’t interfere too much, both parties need to listen but the operating partner needs flexibility to implement their ideas, to take ownership

- A robust agreement – discuss and set out contingencies and expectations from the outset.

New Entrants to Farming Programme

There is a network of new entrants across the country at various stages of developing their businesses. You can join in:

- www.facebook.com/NewEntrants

- www.fas.scot/new-entrants/

- Regional workshops

For more info contact Kirsten Williams, Consultant, SAC Consulting, Clifton Road, Turriff, 01888 563333, Kirsten.Williams@sac.co.uk

There are useful free resources on this website too:

- Case studies—learning from the experiences of other new entrants.

- Guidance notes—benefit from advice tailored to assist new entrants to farming.

- Also see www.gov.scot/Topics/farmingrural/Agriculture/NewEntrantsToFarming

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service