How to Spot Q Fever and What Action to Take

12 February 2024

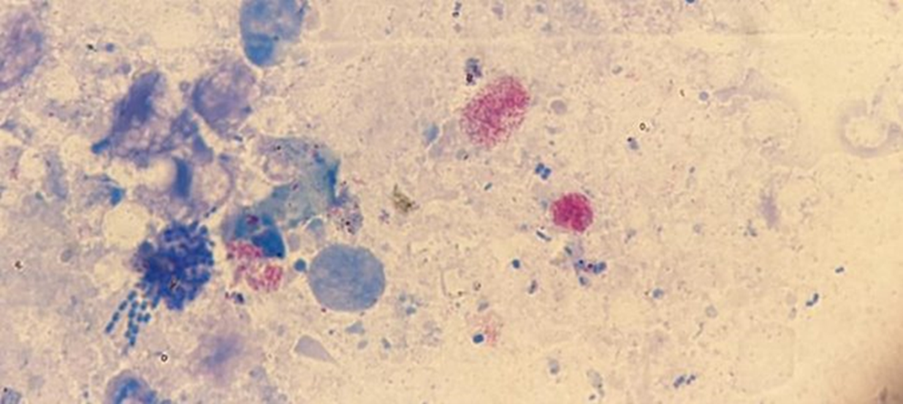

The disease Q fever is caused by the bacteria Coxiella Burnetii which can infect cattle, sheep and goats. It can also cause disease in humans, usually with ‘flu-like’ symptoms which can occasionally be severe and long lasting.

The main clinical signs seen in ruminants are abortion as a result of placental damage. Very often in cattle the abortions will be sporadic but with numbers adding up over time. In sheep and goats this may also be the case, however ‘abortion storms’ may occur - for example in a compact lambing period with close sheep-to-sheep contact.

SRUC Veterinary Services have diagnosed Q fever as the cause of a higher than expected still birth rate in dairy herds, particularly in heifers that are reared away from the main herd returning for calving. There are also reports of Q fever being the cause of more subtle disease in herds such as infertility.

Onward disease spread both to other animals and humans is most likely to occur at the time of birth, including still birth or abortion, with the bacteria shed in large amounts in the placenta and uterine fluids. This can contaminate the environment as well as spread directly and the bacteria can survive for long periods of time in the environment.

The dilemma of the disease is that:

- Clinical disease such as abortion is less common, although under-diagnosed.

- There will be sub-clinical effects that may vary from farm to farm.

- There is the potential for human disease which is likely to be under-diagnosed.

- Infection may be quite common, particularly in dairy herds.

How do we see a way through this?

There are some sound guidelines available which are as follows:

‘In order to harmonise the reporting of Q fever outbreaks in domestic ruminants, it is proposed that a herd/flock be considered as clinically affected when serial abortions have occurred, the presence of C. burnetii is confirmed by Polymerase Chain Reaction from animals having aborted, and when serology in affected dams is positive. Differential diagnosis with other abortive agents is essential.’

For any herd or flock, abortion and still birth should be investigated in conjunction with your vet (every time it occurs it is an abnormal event). This is particularly important for still births in heifers where this outcome might easily be explained away as more likely to occur.

Basic testing for Q fever is carried out on all abortion submissions - PCR testing can be carried out as required and this approach allows for consideration of the full diversity of abortion causes. This can then be considered with your vet as part of the health planning process.

In dairy herds screening can be carried out on bulk milk which is simple, however it is important that the results are considered in the context of the clinical presentations on farm with your vet. This option is not available for beef and sheep systems, which emphasises the importance of abortion testing.

Disease Control

A diagnosis of Q fever should be reported which triggers a supportive advisory process from health professionals to help reduce the risk of human disease transferred from farmed animals.

As abortion will be the main clinical sign, investigate any late term abortions that might occur in your herd and flock. These are unexpected events that are best looked into to rule out the possibility of all infectious diseases including Q fever. Talk to your vet about the best means of investigating these abortions. Don’t forget that negative results are good things as they help rule out infectious diseases as well as rule them in.

Finally of you are working with ruminants and are concerned about chronic flu-like symptoms, contact your doctor to discuss things further.

Colin Mason, SRUC Veterinary Services

Sign up to the FAS newsletter

Receive updates on news, events and publications from Scotland’s Farm Advisory Service